Unaided night vision even now in the 21st century is still the subject of some controversy.

For those just looking for an executive answer as to what supplemental lighting should be used to reduced the recovery time back to night vision (dark adapted or scotopic) here it is: a fully dimmable white light! This of course is a very incomplete answer but so are the answers red or blue-green and you should know why.

Lets start with red, specifically what I will call the red light myth.

I believe the myth started in the photographic darkroom.

Until about 1906 most photosensitive material (plate, film, and paper) was not very sensitive to red. Some of these orthochromatic materials are still used. This allowed these materials to be dealt with for a short time under a relative bright red light because the human eye can see red if the level is bright enough. The fact that L.E.D.s (having a number of advantages over other light sources) were economically only available in red for some time has also help to perpetuate this myth.

As more research about the eye was done it was found that the structure responsible for very low light vision, the rods, were also not very sensitive to red.

It was assumed then that like film you could use red light, which is seen by the red sensitive cones (there are also blue and green sensitive cones to give color vision), without affecting the rods.

It takes a while for true night vision to be recovered. About 10 minutes for 10%, 30-45 minutes for 80%, the rest may take hours, days, or a week. The issue is the chemical in the eye, rhodopsin - commonly called visual purple, is broken down quickly by light. The main issue then is intensity; color is only an issue because the rods (responsible for night vision) are most sensitive at a particular color. That color is a blue-green (507nm) similar to traffic light green (which is this color for a entirely different reason). It would seem that using the lowest brightness (using this color) additional light needed for a task is the best bet to retain this dark adaptation because it allows rods to function at their best.

Unfortunately there are a number of drawbacks using only night vision.

Among these are:

- The inability to distinguish colors.

- No detail can be seen (about the same as 20/200 vision in daylight).

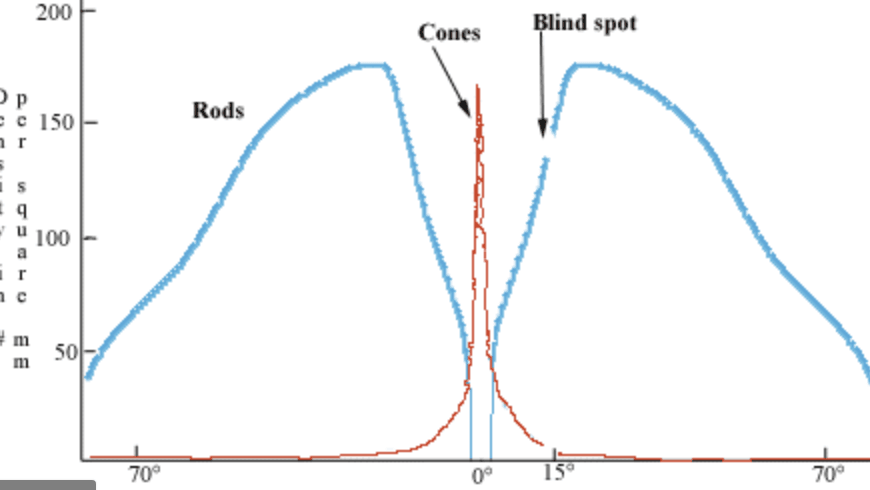

- That nothing can be seen directly in front of the eyes (no rods in the center of the retina), you must learn to look about 15-20° off center.

- Only motion can be detected well, therefore you may have to learn to move your eyes to detect something that doesn't move.

- Objects that aren't moving appear to move (autokinesis). This has probably led to a number of plane crashes.

If you need to see directly in front of you or see detail you need red. Like many myths the red light myth has some basis in fact. The red truth?

Why red? The center 1.5% of your retina (the fovea) which provides you with most detailed vision is packed almost exclusively with red sensitive cones.

This is the same area that has no rods and is responsible for the night blind spot. There are fewer total green sensitive cones than red. The number of blue sensitive cones is very small compared to green and red.

Which is just as well since the lens in the human eye cannot focus red and blue at the same time. And using green really only changes perceived brightness because of the way the signals are processed in our neural pathways. Unlike a digital camera, more pixels, in this case, doesn't give us more detail.

Chart showing the distribution of rods vs cones. Note the absence of rods in the center and the absence of both about 15° away from the the center toward the nose where the optic nerve passes.

At first glance the tendency would be to pick the hue of red at which we are most sensitive (566nm) which would make sense except for the real reason: we don't want to involve the rods. The reason is the rods share the neural pathways with the cones so that you have this fuzzy image overriding the detailed one. This effect disappears at slightly higher mesopic levels which is why white is a good choice for most tasks. Many people look at the numbers for sensitivity for rods and cones and forget that in most cases the numbers have been adjusted so that rod peek sensitive matches cone peak. Rods are in fact sensitive well into the infrared (not too useful except to know that light you can barely sense can adversely impact your night vision). The key then is finding a hue that we can have at a high enough intensity that we can see the detail we need without activating our rods to the point were they obscure that detail. Most source say this should be nothing shorter than 650nm. Experimentation shows a L.E.D. with a peek around 700nm seems to work best (perceived as a deep red). Note that red may be fatiguing to the eyes.

Conclusions:

- No matter what your color choice it must be fully adjustable for intensity.

- If you need the fastest dark adaptation recovery and can adjust to the limitations, or everyone in your group is using night vision equipment then blue-green.

- If you must see detail (reading a star chart, or instrument settings) and can lose peripheral vision (see note 1), then a very long wavelength red at a very low level. Red really only has an advantage at very low levels (were the night blind spot is very obvious).

- A general walking around light so that you don't trip over the tripod, knock over equipment or bump into people, then blue-green with enough red added to get rid of the night blind spot, or maybe just use white. Blue-green at higher brightness also works very well and at a lower intensity than white.

- If you need to see color and detail then likely the best choice is the dimmest white light for the shortest amount of time.

- If you are in the military you must follow their rules; hopefully they will have a good course in unassisted night vision.

- If you are a pilot and say you only fly in the day, you should be aware of the problems of night vision and should consider a basic (ground) course in night flying.

- If you wonder why no one else has drawn these conclusions look at the dashboard of most cars. The markings are large, the pointers are large and an orange-red (a compromise, for certain "color blind" persons) and at night it is edge lit with blue-green filtered fully intensity adjustable light.

For Best night vision:

- Be sure you are getting enough vitamin A or its precursor beta-carotene in your diet (needed for the visual purple).

- Green leafy stuff is best followed by vegetables that have an orange color. Yes that includes carrots but spinach or dark leaf lettuce are better. It is possible to get too much vitamin A especially as a supplement.

- Keep up your general health. Smoking is also very bad for night vision, as are most illegal drugs and some prescription drugs.

- Keep you blood sugar level as even as possible. No meal skipping. Six small meals are better than three large meals. For carbohydrates favor starches (potatoes, rice,and bread) over simple sugars (sweets, alcohol).

- Use dark neutral gray sunglasses, that pass no more that 15% in full sun, when outside during the day.

True night blindness is rare. Most of what people call night blindness is either a lack of vitamin A in the diet or a failure to understand the night blind spot.

Cataracts, even minor ones, increase the effects of glare at night and the eye's lens does yellow and passes less light as we age which may contribute to what some call night blindness.

Note: The red filtered light at the intensity most people use is likely decreasing night vision much more than a properly dimmed white or blue-green light would!

Note: There are day blind spots also but are in a different position in each eye so are less of a problem.

Note: Blue-green (also called cyan, turquoise, teal and other names) as used here is NOT the combination of two colors but is a single particular hue. I use the most common name for that hue.